Visualizing seasons: drawing the year

Background

There is a long tradition in the social sciences and humanities – from anthropology to sociology or natural resource management – of asking individuals and groups to ‘draw their seasonal year’ (see e.g. Bourdieu’s classic ‘Outline of a Theory of Practice’, and a collection of essays about representing the year (external link)).

Drawing the year helps people visualise and make explicit their taken-for-granted temporal structure of the year; the events, signs and rhythms that mark the passing of the year, and the way their activities are divided into seasons, workweeks, holidays, and so on. Drawing the year helps study, compare and make sense of peoples diverse frameworks for organising time, and the ways they may be evolving. Producing a visual record of the year also enables people to play with and reorganise frameworks; to change timings.

What is clear is that people conceive of the (seasonal) year in dramatically different ways. Asking people to draw the "shape" of their year can yield surprising results, as seen in a study organised by a Norwegian newspaper. (external link)

The visual representation of time is highly cultural, so that in European traditions the year is often drawn as a circle like a clock, with each of the 12 Gregorian months corresponding to a number on the clock.

Circular year drawn by a school student in Bergen in 2019:

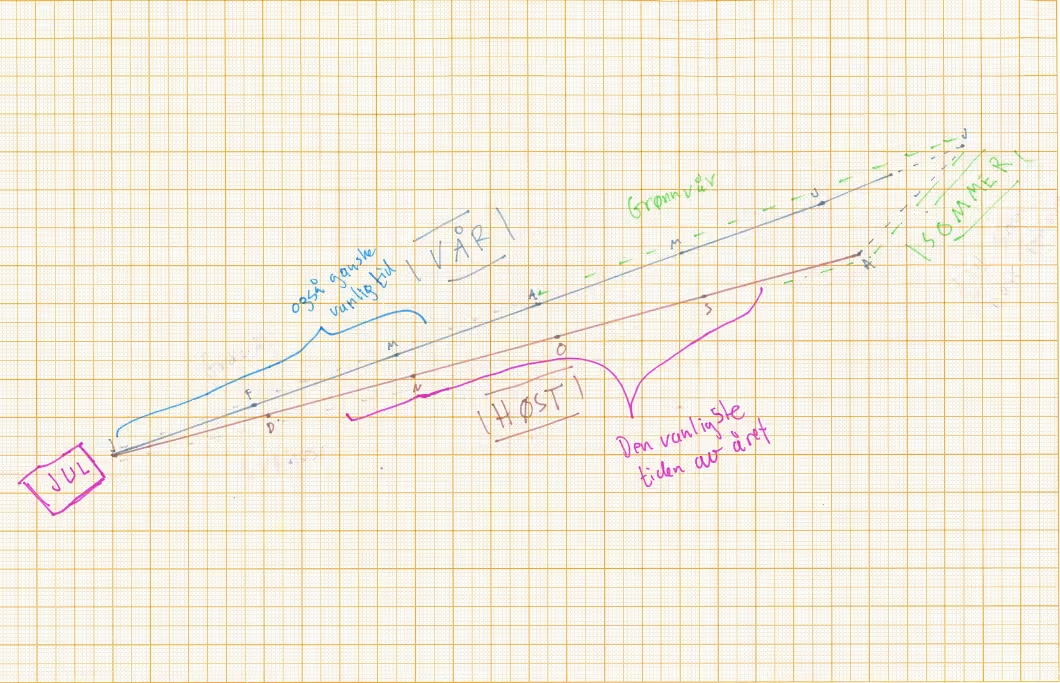

But other representations abound, from graphs to mobius strips, landscape maps, sundials, rhombus and other more irregular (amoebic-like) shapes.

Other studies have tried to access other (indigenous) cultural representations of the year, such as the "cold-fire" calendar of Indigenous Australians (external link), marked by the life-cycles of plants and animals, or the Anishinabek Nation "turtle calendar", read from the 13 segments of a snapping turtles shell, each corresponding to one of the 13 moons in their lunar calendar.

One common distinction across calendars, for example, is between seasons as concrete "blocks" of time with hard boundaries, or seasons as rhythms or cycles that flow through the year.

Wave year illustrated by project member Arjan Wardekker

Objectives

- To invite individuals and groups to reflect on how they perceive the temporal organisation of a seasonal year through drawing it (using different media).

- To compare and contrast the diverse ways of visually representing the year, for an appreciation of the different ways of seeing and acting "on time".

- To discover what (if anything) is common across diverse visualisations of the year, as shared temporal reference points that people coordinate around.

Requirements:

- Drawing can be part of an interview with an individual, up to a group activity, or even as a ‘drop-in’ activity where hundreds of participants take part in a period.

- Facilitation: This activity demands little facilitation, and a single instructor is usually enough. If using different media (e.g. carving in wood) this may demand further instructors skilled in the media and techniques.

- Timing: How long the activity takes depends on ambitions. Where participants ‘drop in’ – at a stand at a science fair for example – they may take only 10

minutes. Where drawing is part of a workshop, this may take a whole day. - Resources: This depends on the medium. Most simply it requires paper and pens (ideally different coloured pens), and a place to draw. But activities can be run with other media, such as carving the year in wood, requiring additional resources.

- Free drawing versus a template: Free drawing requires only blank pieces of paper, but using prepared templates can facilitate the activity and make the drawings more comparable. It is best to use a culturally recognisable template, e.g. CALENDARS work in Norway asked groups to carve or draw their version of a traditional ‘primstav’ or plank calendar, fitted to the plank-shaped template. A template found useful in CALENDARS was to use a circle marked with Gregorian months like segments of a pie, as well as the two solstices:

Method:

- The activity can begin with a blank sheet of paper, asking participants to draw the shape of their year, comprising the seasons, before presenting them to each other. The advantage of this step is that participants are not constrained by widespread

cultural frameworks and can fully appreciate the diverse ways of visualising time. This usually means starting with examples of other people’s pictures to encourage participants to think laterally. The activity can stop here or move to Step 2. - Depending on time, the activity can hop over Step 1 and begin here. In Step 2 participants are presented with a template (see Requirements) and asked to fill it out with temporal reference points – events, periods, cycles - that mark the passing of the year, by drawing or writing in these markers. CALENDARS used a circle template and ask participants to populate it with ‘natural signs’ (e.g. flowerings, storms), socio-cultural events, and activities/things-they-do. After this step, participants are asked to observe the pattern of temporal markers and divide the year into seasonal periods. The activity can stop here or go to Step 3.

- This activity finishes with participants sharing and comparing their filled-out templates. This discussion makes clear the diverse temporal organisation of people’s years. One important final step is to distil what – if anything – is common across the diverse pictures of the year. For example, are there cultural festivals that provide a common reference point for the passing of the year? While there are diverse ways of perceiving the seasonal year, society needs some key points of reference to synchronise activities to.