Spring semester 2023: Meet our guest researcher Dr. Ariela Marcus-Sells

Dr. Ariela Marcus-Sells is a guest researcher at the MprinT project in the spring semester of 2023. She is currently an associate professor in religious studies at Elon University in North Carolina. Her work focuses on the intellectual history of Muslim societies in West Africa. In particular, she has been part of a new wave of researchers who study texts and traditions that have been described as “magic” or “occult” and discuss these as part of a broader knowledge tradition within Islam.

Published: (Updated: )

Interview with Dr. Ariela Marcus-Sells

Q: You have been among a group of scholars who have taken seriously the role of texts that earlier scholars simply labelled as “magic” and thus not part of the “grand” Islamic tradition. Why do you think this was the case before, and why do you think this is now changing?

A: In earlier research these texts were excised from the field of Islamic studies. This was partly because of the orientalist and colonial framing (and its protestant antecedents) which attempted to erect firm boundaries between science, religion and magic. There was also the element of racism; “magic” was a label for othering.

We are now coming off a couple of decades of post-colonial criticism which has undermined these old assumptions in the field of religious studies and which has tackled these old framings. After deconstructing a previous frameworks, it takes some time to build a new one. How can we approach knowledge systems within Islam (in this case) which does not fit easily on to these categories? What categories should we use instead?

My work – and that of others - build on excellent progress done in the study of Mediterranean and early/early modern European history that has sought to investigate how the category of magic has been labelled onto marginalised peoples. At the same time, this research has also brought to light how this type of knowledge was claimed by certain groups to shape and maintain their identity. In other words: What this research has shown, is that magic has entered into parallel discourses, aimed at exclusion and at claiming.

But why this surge now in the study of magic? I think it has to do with the cultural moment we find ourselves in. The synergy between knowledge and practice, we are now asking ourselves where they come from and how do we define them. We are asking questions about true knowledge (who defines it, and who has access to it) and how this translates into efficacious practice, for example in medicine, practice, self-help, hygiene, being a “good person”, improving the world, your family, your community etc. How do you know what works and what does not? What is that authority based on?This mirrors discussions in the past, and this is when we tend to ask these questions about the past. Such questions are never completely answered in any society. They permentantly challenged and contested. Fundamentally, from a humanistic framework, these are questions related to what it means to be human in a specific culture and a specific time.

These questions also form the theoretical framework of my book. What happens when someone tries to draw a boundary between “true” and “false” knowledge. The very act of doing so is what binds the drawer of the boundary to the opposing view. The two arenas are paradoxically reinforced. The discourse allows for these sites of challenge.

Q: As you have seen, texts that fall into the very broad category of “magic” also make up a substantial proportion of the MprinT corpus. At the moment, we do not yet have sufficient overview to give a percentage (it is somewhere around 15%). The vague number is partly because classification of such texts is hard to do. The line between Sufism, prayer collections and medicinal works and “magic” is hard – if not impossible - to draw. Miracles abound in Sufi narratives, amulets and incantations contain well-known prayers and healing practices often have elements of magic. Are these classification issues itself an indication that a differentiation between the sciences (ʿilm) and sorcery (sihr) is an outside (etic) attempt to introduce divisions where none existed?

A: There were times and regions where there was no division. There were other times and places where scholars tried to impose such divisions. Political leaders – rulers – would also try. But even when they attempted to make such a division, their classifications were never clear.There is no one category that applies with a strict definition across space and time, nor was there ever a classification system that was universally accepted. This poses a problem for us as historians and cataloguers. If you choose an emic scheme, and impose a second-order classification, then you are choosing one voice over possible other voices. If you choose an etic scheme (say, for example “magic”) then you are choosing a framework from outside of the tradition, imposing a label that was not there. There are challenges with both. From within the tradition, the challenge is that since there is no one term, you actually create a fragmentation within the library or archive. You create the impression that certain things (like duʿāt and talismanāt) were completely separate categories when in fact they were closely linked.

Creating such separations will make it harder to both search across fields but moreover, to actually visualize a discourse that was in fact not bounded by discreet genres. Etic terms are not necessarily bad. They can be very useful for making sense of a cultural field beyond the kind of emic, technical terminology.

Sufism is itself an example. It is an etic term. There was no word for “Sufism” in the classical tradition. Rather, what we now know as “sufism” was a set of ethical guidelines on how to be a good Sufi. “Taṣawwuf” applied to this genre would have excluded literature of manaqib, silsila literature etc. So, having a heuristic term like Sufism/taṣawwuf helped focusing attention on a cultural current within Islam and gave rise to a whole field of research.

When it comes to magic, these terminologies are still being actively debated - unlike Sufism. The esoteric, the occult, the magic, sorcery, the unseen… (I am partial the latter term). To be honest, I am not sure we will get to the same level of terminology as we have for Sufism. This is because Sufism and its terminology was based on “a sufi” which is a emic term for a person, an individual identified as such. There is no comparable observable term for a “sāhir” – a sorcerer. There is also the fact that we have so many disparate, fragmented emic terms which in turn fragments the literature We are tied to the literature we study.

Q: In your book, you engage with the works of the Kunta scholars. Did you at the outset consider their textual production as either science or “magic” – i.e. did you make attempts at categorizing their works?

A: I started by trying not to impose framework but determine from within their writing. The question of sihr/magic versus ʿulūm/science derives from their own texts. Especially Sidi Muhammad, who spelled it out: Some scholars consider this specific practice to be sorcery, but, he says, they are not. Rather, he says, it is one of the ʿulūm al-ghayb (sciences of the unseen), and then proceeds to outline the sub-categories within them. He clearly defends it as a branch of science/ʿilm. His father is more concerned about the ʿilm itself and how it is to be accessed.

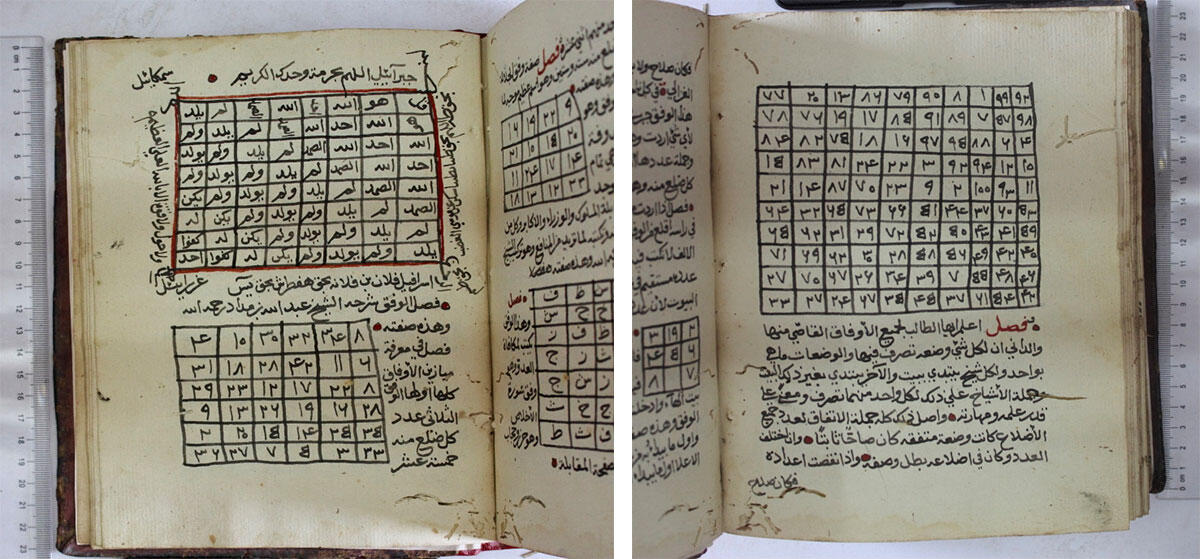

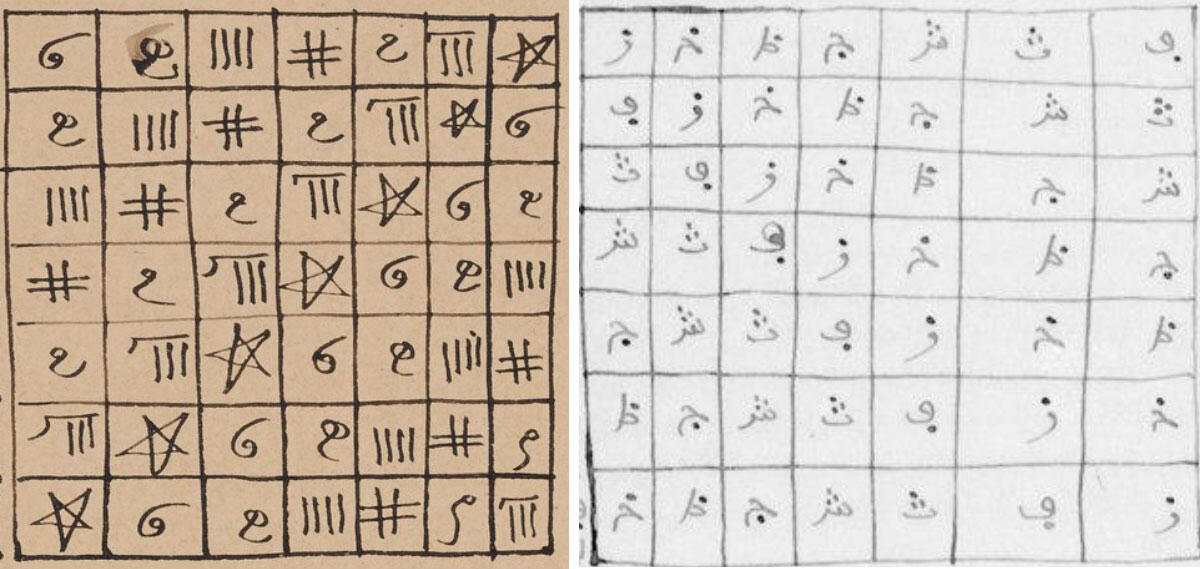

When I started, I did not assume any prior meaning to technical terms (like the magic squares or incantations/ruqya which Sidi Muhammad defines as a type of speech that produces healing. This was very challenging without preset definitions for the vocabulary! However, it often turned out that the Kunta too were using a common set of definitions, from the 13th century Egyptian scholar al-Buni etc. I really tried to avoid assuming that the Kunta were using preset categories – but the fact is that they often did. Trying to suspend assumptions about meaning was incredibly time-consuming.When I tried to decipher these texts in the 2010s there was not a lot published on this topic. My book came out in 2023 and by then there was a whole field emerging!

Q: In terms of cataloguing, we are trying in MprinT to stick with emic categories, such as fiqh, tawḥīd etc. However, this is complicated when it comes to the more occult texts, as no one emic category exists. Duʿāʾ, dhikr, ṭalismanāt, fawāʾid, siḥr, ṭibb, manāqib – these are all terms that are in use. They may change over time and with location. In your experience, what is the best way to go about this? Ideally without spending too much time on simply description…

A: Here is a very concrete suggestion: Create a primary category as the closest emic term. If you have a search field that is something like “comments”, I would choose one heuristic term that can signal to researchers that this is related to the field of the occult – an etic term. “ʿIlm al-ghayb” could be one such term. Whatever you choose, carefully define and discuss it on the site where the catalogue is hosted. This can now be done with reference to specific framework, as for example done by Liana Saif or Bernt Christian Otto. The important thing is that it is carefully argued and made transparent to other researchers who can understand why this term is chosen. A: Problems are also aplenty when it comes to authorship, or they are compilations assembled at unknown times. In your experience, what ways do we have to attribute authorship or date these manuscripts?

This is a massive challenge. Large parts of these works are either unattributed (no specific author) and they are undated. In order for a researcher to say anything about them, you need to tie them to historical context of some kind. I think putting work into the historical context (like by pinpointing the copyist is space and time) might help us going past the question of authorship. These texts are most often bricolages and there are many misattributions and deliberate forgeries. It is in fact more interesting to know where, when and why these copies were produced rather than who composed them in the first place. To achieve this, we need a much more concerted effort on paleography. Paleograhy was so central to the study of European text, especially for situating them in context. If we made only a fraction of this effort on the African Islamic manuscript tradition, we could make huge strides.

I think the main questions we should ask are: What material has lived on? How has it been re-contextualized and interpreted anew – and why? And conversely: What was discarded or abandoned and why?The fact that the author then has to feature as “unknown” is less of a problem in this context. Very often, this is anyway attributed. What will you do for example when an early printed copy of al-Bunī’s Shams al-Maʿārif al-Kubrā turns up in your MPrinT corpus? We know that it is attributed to al-Bunī, and it would say so on the title page. We also know that it was not authored by al-Bunī. Maybe it should be part of the title: “Shams al-Maʿārif al-Kubrā by al-Bunī”? In any case, the interesting point is that it was circulating in this particular region at this particular time.