Pottery and soapstone finds from Borgund

In the late nineteenth century the great Arts and Crafts designer, social reformer and devotee of the Nordic Middle Ages, William Morris, called pottery “the most ancient and universal, as it is perhaps (setting aside house-building) the most important of the lesser arts”.

By: Mathias Blobel

Published: (Updated: )

Despite his deep interest in the Middle Ages, Morris was not an antiquarian. He did, however, grasp the importance of pottery studies for antiquarianism, the discipline that would later become archaeology. He went on to say that the art of pottery was “one, too, the consideration of which recommends itself to us from a more or less historical point of view, because, owing to the indestructibility of its surface, it is one of the few domestic arts of which any specimens are left to us of the ancient and classical times.” As Morris correctly understood it is the resilience, as well as the relative fragility of pottery that makes it ubiquitous in the archaeological record and that has rendered it one of the most important categories of finds for establishing chronological sequences, as well as the type of find, besides human remains, that is probably most associated with archaeology in the public mind.

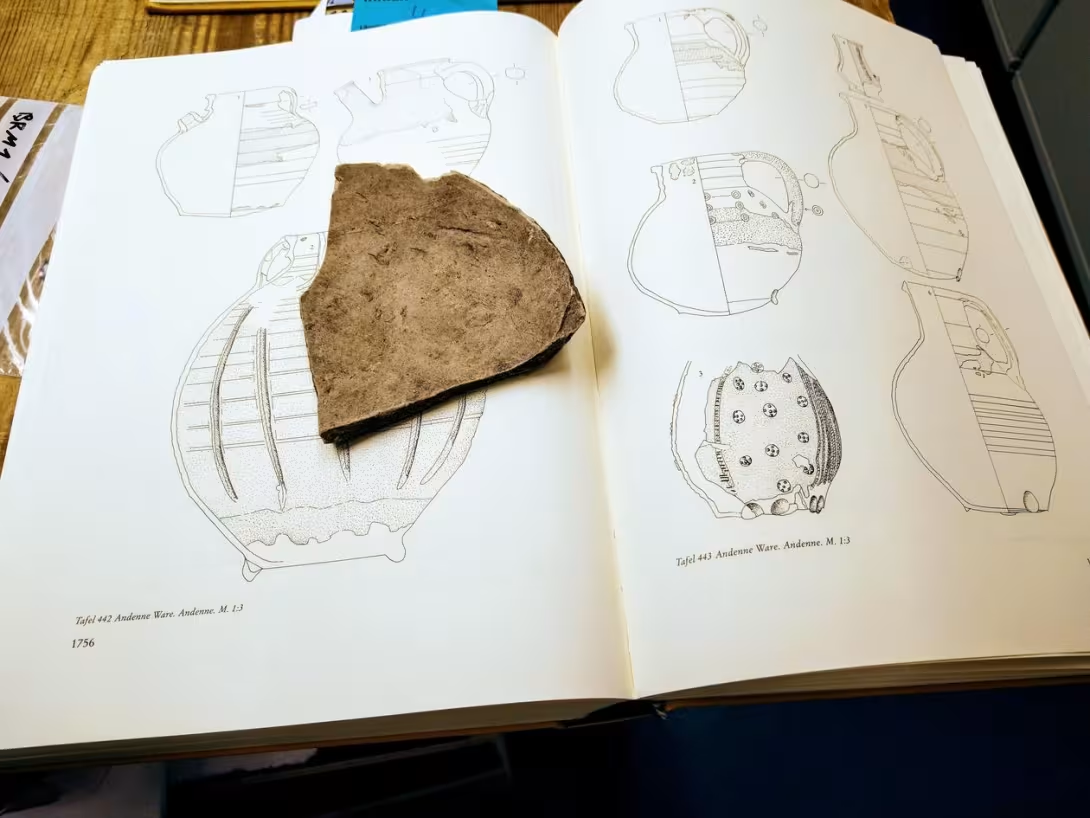

This week for the blog we are taking a closer look at the pottery and soapstone finds from Borgund. In keeping with other town sites in Norway pottery makes up a large amount of the finds spectrum in Borgund. At first count c. 10,000 individual sherds of pottery are registered in the project database. In the Middle Ages pottery was not produced in Norway, the need for cookware, tableware and drinkware was rather filled by importing pottery from established large-scale production centres in Germany, England, France and the Benelux region. In addition to these imports, locally produced cooking pots carved from soft soapstone would have been a ubiquitous sight in medieval Norwegian kitchens and vessels made of glass, metal and wood would have graced the tables alongside the ceramics.

All in all the Borgund excavations have yielded c. 600 pieces of soapstone that can be identified as having come from pots. Investigating these two categories of finds, pottery and soapstone vessels, is the purview of one of the BKP’s two PhD projects. It is what I spend my days doing. Chronology is without a doubt one of the most important roles pottery serves in archaeology, and in the BKP the establishment of a chronological sequence is a major aspect of work with this category of finds. However, pottery and soapstone can tell us much more about the past than just when things happened. The vessels made from these two materials had to be brought to Borgund; in the case of pottery from far-away kiln sites in the south and in the case of soapstone from quarries in Western Norway. These sherds thus serve as witnesses of trade. Because in many cases we know their points of origin and where they ended up, Borgund, they can be used to reconstruct trade networks both international and domestic.

As we know from other studies in Norway and elsewhere, the decorated pottery of the high Middle Ages could also serve to signal their owners’ socio-economic status or even a regional or national identity. Furthermore, drinkware and especially kitchenware reflect changing practices in cuisine and in habits of consumption.These questions and many others can be approached on the basis of pottery and soapstone material that can be properly identified and provenanced through typological and geochemical means. Traces of sooting, food incrustations and general use wear can aid in reconstructing cooking practices.